What if you financed a car though Honda, but they decided to continue charging you “maintenance fees” surprisingly equal to your car payment at the end of the financing agreement despite you having completely paid the balance? Or perhaps you have car insurance through Geico and they insist on charging you not only the cost of their service, but a car payment as well, even though you never bought a car from them and you own your car flat out? Would you let Comcast dictate which TV or computer you can use? You would deem these practices unacceptable and take your business elsewhere. Yet we condone this behavior with our wireless service providers by paying them every month.

To understand the analogy, let’s look at how the wireless industry of the US works right now.

If I’m like the vast majority of cellular service customers in the country, when I want a new phone, I go to my carrier’s retail store or website and buy one. Only, I don’t actually *buy* my shiny new phone in the sense of the word; I finance it with a subsidy and a two-year service contract that guarantees my carrier receives the money they put forth to subsidize my device in the first place. When I buy my new phone for, let’s say $200, that’s actually a down payment on a $650 phone, followed by a two-year contract’s worth of payments toward the complete cost of the phone.

$650 minus the $200 down payment leaves a remainder of $450, assuming the carrier doesn’t get the phone at a discounted bulk rate. The remaining balance over the course of a twenty four-month service agreement can be split into $18.75 a month. The carrier has to be profitable so let’s bump that up to $20 a month so they can grab 5% interest. So far, that seems rather fair.

The disruption occurs, however, when I either bring my own phone or I complete my contract. Verizon and Sprint won’t let me activate a phone they didn’t sell, period. I can never buy a Cricket phone and activate it on Verizon, even though the network technology is identical and the phone is physically compatible. I can’t even take a Virgin Mobile phone (though Virgin is owned by Sprint and runs on Sprint’s network) and activate it on Sprint. Just like aforementioned hypothetical scenario in which Comcast gets to choose which TV or computer you can and can’t use with their service, we allow Verizon and Sprint to decide what device we can and can’t use.

But let’s say I own an unlocked Galaxy S3 that I want to activate on AT&T’s network. By bringing my own device, I just saved AT&T a couple hundred dollars on a subsidy because I didn’t finance my phone through them. There is no risk on their part because I brought my own handset. Yet, when I do so my bill is the same as that of someone who purchased their device with a subsidy. Why should my bill pay for a phone I didn’t finance? That’s like an automobile insurance company charging me a car payment in addition to the cost of the insurance despite my having brought my own car to the service, so to speak.

The same thing occurs when I reach the end of a wireless contract. The contract is in place for the carrier’s protection: If they are going to lend me $450 for a shiny new iPhone, they need a signed legal document to ensure that they have a means of recovering their cash. That part is fine, but what isn’t okay is that when I complete that contract, the carrier is absolving me of my obligation to pay them, and the only reason a business will let me off the hook is because I have already paid what’s due.

So my contract is complete and I have paid off my phone, but yet, my bill stays the same. They are still charging me for a phone I’ve paid off, but now it’s all profit. They’re just pocketing the difference. If I choose to keep the same device to save money instead of buying a new handset, or maybe buy a pre-owned device from a Craigslist seller, I’m still forced to make payments on a phone I own just to stay connected.

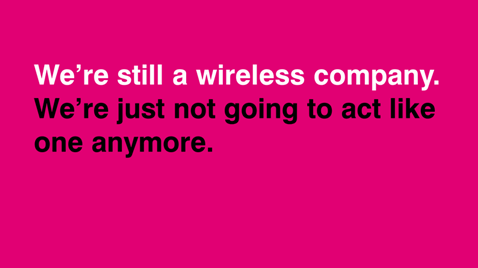

Enter T-Mobile. With the Uncarrier initiative, the folks at T-Mobile are dropping anticompetitive service contracts and separating hardware and service costs. When you pay off your phone, you own it and your bill drops by a pre-disclosed dollar amount because, well, you shouldn’t have to pay for something you own. Your phone can also be unlocked so that if you’re displeased with the performance of the network, you can go to whatever GSM carrier you desire. T-Mobile are also allowing customers to bring whatever GSM handset they desire to the network and are even modernizing the network to allow full compatibility with international/unlocked AT&T handsets.

T-Mobile has recently come under fire, however, for their advertising of the new Uncarrier plans as ‘contract-free.’ According to CNet, Washington State Attorney General Bob Ferguson finds T-Mobile’s promise of no-contract service to be a misnomer, citing that if a customer purchases a device from T-Mobile with financing but decides to leave T-Mobile before the device is paid in full, they must then pay the owed balance of the device.

Ferguson’s ruling holds some water, considering that in a sense, though this is strictly a financial contract, it is still a contract. There is no ETF, per se, but rather, the customer *does* need to pay the remaining balance of the device. T-Mobile reached an out-of-court agreement with Ferguson, willingly complying with the Washington AG’s ruling by agreeing to discontinue advertising it’s service with no restrictions.

Even bearing this in mind, T-Mobile is breaking away from the established status quo by being upfront with customers and separating the cost of hardware and service, something its larger competitors have yet to do. Unlike Verizon and Sprint, and even smaller carriers who operate similarly to T-Mobile, when a T-Mobile phone is paid in full, the device is unlocked and can be used with any GSM carrier.

The only way we are going to see change and true competition in our wireless industry is to show the carriers that their practices are unacceptable by voting with our dollars.